In one of my previous post on this website, I had discussed about Reactive Programming, and how we can implement that in Java using RxJava.

In this post, I will be discussing on building a Reactive Spring Boot Application. The application that I will build is going to be a very simple Restful API, which will have two endpoints. One endpoint will fetch the data synchronously. Another endpoint will fetch the same data asynchronously.

In case you need a very quick overview on Spring Boot, you can check out here.

🎯 Libraries available for Reactive Programming in Java

Among popular Reactive Programming Libraries for Java, the three most frequently used libraries are:

- RxJava

- Reactor

- Java 9 Flow Reactive Stream

In this article, I am going to use Reactor, from Project Reactor.

🎯 Reactor

Spring is known for creating wrappers around the underlying specification, and offer easier integration of those specifications in Spring Applications.

In case you are wondering what is Reactor, this is what the official documentation states:

Reactor is a fourth-generation reactive library, based on the Reactive Streams specification, for building non-blocking applications on the JVM.

With Reactor, we get seamless integration of reactive programming in our Spring applications.

As part of Project Reactor, we get several modules that we can include in our application. Each module has its own purpose to fulfill.

I will be working with Reactor Core and Reactor Netty mostly in this article.

🎯 Prerequisite concepts

Before we dive into the implementation, lets revisit important underlying concepts around Reactive Programming and Reactive Systems.

1. Reactive Programming is not Reactive System in itself.

Reactive programming is development model structured around asynchronous data streams.

Reactive Manifesto defines what are Reactive Systems. It is an architectural style to build responsive distributed systems. The manifesto mentions of four key properties:

Responsive: A reactive system needs to handle requests in a reasonable time.

Resilient: A reactive system must stay responsive in the face of failures (crash, timeout, 500 error etc), so it must be designed for failures and deal with them appropriately.

Elastic: A reactive system must stay responsive under various loads. Consequently, it must scale up and down, and be able to handle the load with minimal resources.

Message driven: Components from a reactive system interacts using asynchronous message passing.

Just by including reactive programming in our application, the application doesn’t become a Reactive System. For an application to be a Reactive System, it must obey all the properties mentioned by the Reactive Manifesto.

2. Thread Per Request Model

Application servers create a new thread for every incoming request.

When a request comes to the server then a new thread is created. For a blocking call, this thread synchronously executes the instructions as part of processing the request. It needs to wait for IO operations like getting response from some external API, or to get response from the database, etc. It stays blocked, until the response arrives to it. Meanwhile, if another request comes in to the server, the server creates a new thread again to process that new request.

Usually, there is a limit to the number of threads that can be created in the server, which is decided by the Thread Pool limit for the server. Beyond this limit, no new threads can be created. So its evident that no new request will be served once the thread pool limit is reached.

Also, thread creation is costly. So to keep creating new threads for every incoming request doesn’t seem to be a correct. Right?

Reactive Programming tries to solve this problem. Here the thread from the thread pool doesn’t stay blocked for IO operation. Instead, it executes the instruction and return to serve another request. Once response to IO operation needed by the thread arrives through interrupt or a callback, processing happens, and the service response to the user is returned.

This way, effective utilization of resources is achieved, with bare minimum burden to the application server.

3. Horizontal Scaling

With hardware costs getting cheaper, cloud services becoming cheaper, at first glance it seems appropriate to have more instances put together and the system be horizontally scaled when load increases. But think for a while, there is still cost involved whenever you spin up a new instance.

Why not solve this issue with one instance only?

With asynchronous calls in reactive programming we effectively utilize our threads. This way without spinning up extra servers, loadbalancers, we will be able to manage with single instance of the service only. It makes the whole deal even more cheaper.

4. Backpressure

Backpressure solves the flow control problem in the network.

When the consumer is overwhelmed with the huge volume of data arriving to it for processing, the entire system gets impacted.

In Reactive Programming with non-blocking calls, the consumer can ask publisher to send data in smaller amount which it can handle. It’s like asking I can process 100 elements at a time, give me this much Mr. Publisher. Once I complete processing this 100 elements, send me the next 100. This way, the entire system can stay in motion all the time.

5. Data Flow as Event Driven Stream

In traditional database systems, a thread connects to database and waits until the data arrives. We have event driven database systems now, which make use of reactive database drivers like reactive mongodb, that respond to the request via event stream.

With Reactive Programming, thread from the application makes a call to Reactive Repository of underlying database system asking for data, and then returns. The database system after having collected the data raises another event with the sought data. The thread gets this data through the event stream and then can process it.

This way, database systems also contribute to making the whole IO operation asynchronous.

🎯 Let’s play with Reactor

Start by adding Spring Reactive Web dependency in our maven project. I created the project from Spring Initializr, and chose to have Spring Reactive Web dependency.

In case you are going to add this dependency directly in your pom.xml, then below are its coordinates.

<dependency>

<groupId>org.springframework.boot</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-boot-starter-webflux</artifactId>

</dependency>

Before we start writing the web service, it will be better if we get our hands dirty with few Reactor data types and understand about their key offerings.

We can create a junit test class and start playing.

Let’s try creating a *Mono *and a *Flux *object and try subscribing to them.

Mono and Flux are Publishers in Reactor. This means that they are responsible for publishing the data.

Mono, as per the literal meaning of the term ‘mono’ serves us with only one element.

Flux on the other hand serves with more than one elements. It is a stream of single type of items over time.

@Test

public void testMono() {

Mono<String> stringMono = Mono.just("Big Bang");

stringMono.subscribe(System.out::println);

}

Output:

Output:

Big Bang

Here we have created a Mono object using Mono.just(). We subscribe to this Mono using .subscribe().

@Test

public void testFlux() {

Flux<String> stringFlux = Flux.just("Alan", "Bob", "Mark");

stringFlux.subscribe(System.out::println);

}

Output:

Alan

Bob

Mark

Here we have created a Flux object, which is going to serve us with three String elements.

We can subscribe to this the same way like Mono, by using .subscribe() on the Flux object.

If you try adding .log() to any of the publisher Mono or Flux, you will be able to see the logs printing from various components of the reactor workflow.

Mono<String> stringMono = Mono.just("Big Bang").log();

stringMono.subscribe(System.out::println);

Output:

2022-03-26 21:33:44.770 INFO 13104 --- [ main] reactor.Mono.Just.1 : | onSubscribe([Synchronous Fuseable] Operators.ScalarSubscription)

2022-03-26 21:33:44.785 INFO 13104 --- [ main] reactor.Mono.Just.1 : | request(unbounded)

2022-03-26 21:33:44.785 INFO 13104 --- [ main] reactor.Mono.Just.1 : | onNext(Big Bang)

Big Bang

2022-03-26 21:33:44.785 INFO 13104 --- [ main] reactor.Mono.Just.1 : | onComplete()

Appending .log() to the Flux object.

Flux<String> stringFlux = Flux.just("Alan", "Bob", "Mark").log();

stringFlux.subscribe(System.out::println);

Output:

2022-03-26 21:34:40.049 INFO 24092 --- [ main] reactor.Flux.Array.1 : | onSubscribe([Synchronous Fuseable] FluxArray.ArraySubscription)

2022-03-26 21:34:40.049 INFO 24092 --- [ main] reactor.Flux.Array.1 : | request(unbounded)

2022-03-26 21:34:40.049 INFO 24092 --- [ main] reactor.Flux.Array.1 : | onNext(Alan)

Alan

2022-03-26 21:34:40.049 INFO 24092 --- [ main] reactor.Flux.Array.1 : | onNext(Bob)

Bob

2022-03-26 21:34:40.049 INFO 24092 --- [ main] reactor.Flux.Array.1 : | onNext(Mark)

Mark

2022-03-26 21:34:40.049 INFO 24092 --- [ main] reactor.Flux.Array.1 : | onComplete()

You can see that logs are getting printed from different components of the the reactor workflow. But what are these, and where are they coming from? Let’s try to find out.

🎯 Reactor Core Components

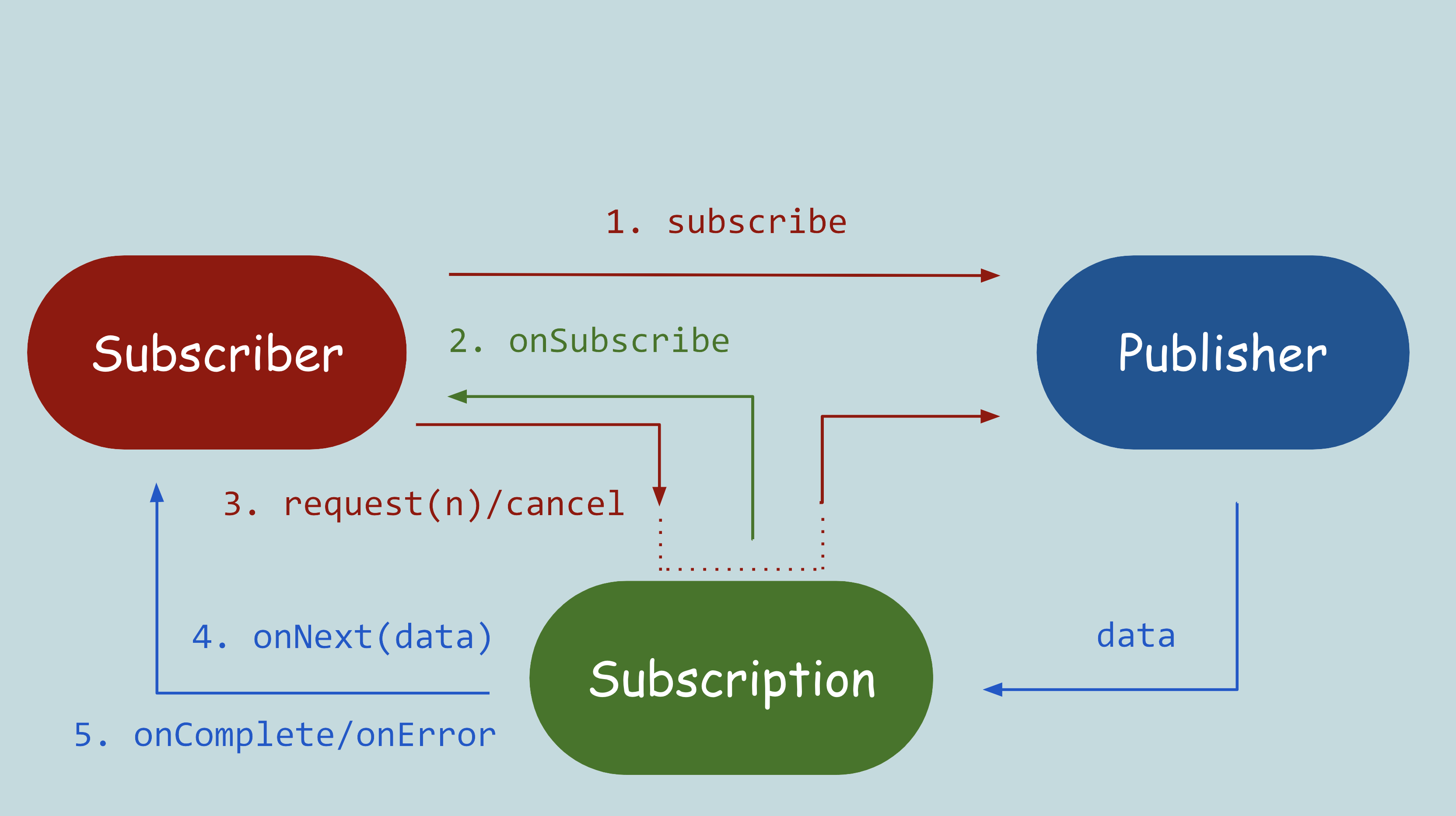

Reactor is comprised of three key components. These are all interfaces:

1. Publisher: This publishes the data. The subscriber needs to subscribe to a publisher in order to get the data from that publisher.

public interface Publisher<T> {

void subscribe(Subscriber<? super T> var1);

}

2. Subscriber: This is the consumer of the data. It has below four abstract methods.

public interface Subscriber<T> {

void onSubscribe(Subscription var1);

void onNext(T var1);

void onError(Throwable var1);

void onComplete();

}

3. Subscription: When we do publisher.subscribe(), a subscription gets registered for us. This subscription represents the relationship between publisher and subscriber.

request() method is used to enable backpressure. By passing the long argument to this method we are asking to provide that much amount of data at once.

cancel() method is used to end the subscription relationship between the subscriber and the publisher.

public interface Subscription {

void request(long var1);

void cancel();

}

The below flow diagram specifies how these three interfaces are inter-connected and how abstract methods declared in these interfaces are getting called, one after the another.

Now, after having seen this flow diagram, I hope the logs that were getting printed in examples above from the test playground makes more sense.

Let’s see how we can handle the error. The syntactical way to handle error is same for Mono and Flux.

In the example below I have explicitly thrown an exception from the Flux. I am handling this exception then at the subscriber level.

Flux<String> stringFlux = Flux

.just("Alan", "Bob", "Mark")

.concatWith(Flux.error(new RuntimeException("Some Error Occurred")))

.concatWithValues("Lucy")

.log();

stringFlux.subscribe(System.out::println, error -> {

System.out.println("Subscriber has received some error: " + error.getMessage());

});

Fair enough. So far, we got out hands dirty with the very basics of reactor in spring boot.

Let’s start writing a simple Restful API in Spring Boot.

Writing the Restful API

Our application will expose two endpoints.

- /v1/api/students: It fetches student details synchronously.

- /v1/api/async/students: It fetches student details asynchronously.

Student class has bare minimum attributes

public class Student {

private long Id;

private String name;

public Student(long id, String name) {

Id = id;

this.name = name;

}

public long getId() {

return Id;

}

public void setId(long id) {

Id = id;

}

public String getName() {

return name;

}

public void setName(String name) {

this.name = name;

}

}

We will start with the controller now.

@RestController

@RequestMapping("/v1/api")

public class StudentController {

private StudentService studentService;

@Autowired

public StudentController(StudentService studentService) {

this.studentService = studentService;

}

/**

* Fetches List of Students synchronously.

*

* @return - ResponseEntity<List<Student>>

*/

@GetMapping("/students")

public ResponseEntity<List<Student>> getSyncStudents() {

return ResponseEntity.ok(studentService.getStudentsList());

}

/**

* Fetches Flux of Students.

*

* @return - Flux<Student>

*/

@GetMapping(value = "/async/students", produces = MediaType.TEXT_EVENT_STREAM_VALUE)

public Flux<Student> getAsyncStudents() {

return studentService.getStudentsFlux();

}

}

StudentService is injected in this controller.

At getAsyncStudents() method, you will observe I have used produces of type MediaType.TEXT_EVENT_STREAM_VALUE. This is required to emit the response as asynchronous event stream.

Now, let’s have a look on the StudentService class.

@Service

public class StudentService {

public List<Student> getStudentsList() {

List<Student> fetchedStudentList =

IntStream.rangeClosed(1, 20)

.peek(element -> System.out.println("Fetched student with id: " + element))

.peek(StudentService::sleep)

.mapToObj(element -> {

int rollNumber = element;

String name = "Student " + rollNumber;

return new Student(rollNumber, name);

}).collect(Collectors.toList());

return fetchedStudentList;

}

private static void sleep(int element) {

try {

Thread.sleep(1000);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

}

We are fetching the hard coded values using IntStream.rangeClosed(1, 20).

In order to simulate the slow IO while fetching the data, I have on purpose used Thread.sleep(1000). After every record fetched, there is a delay of 1 second.

Here, with getStudentsList(), we have a blocking call. Thread will need to keep on waiting until all the data elements are fetched, and the List

So, for our blocking call, we will see that consumer has to wait for 20 seconds before it gets the List of Student.

With non blocking call, we will see that the consumer doesn’t need to wait for the complete list to arrive. Consumer will be getting data as every element gets processed, and is emitted by the Flux.

@Service

public class StudentService {

private static void sleep(int element) {

try {

Thread.sleep(1000);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

public Flux<Student> getStudentsFlux() {

Flux<Student> fetchedStudentFlux = Flux.range(1, 20)

.delayElements(Duration.ofSeconds(1))

.doOnNext(element -> System.out.println("Fetched student with id: " + element))

.map(element -> {

int rollNumber = element;

String name = "Student " + rollNumber;

return new Student(rollNumber, name);

});

return fetchedStudentFlux;

}

}

In getStudentsFlux() method we are preparing the Flux of students. We have added a delay of 1 second as well here to simulate delay in fetching records as part of IO.

One important thing to note is that List

In getStudentsFlux() if we use List

Now when we try to fetch data on endpoint /v1/api/async/students, we will see that we are getting data one by one. The consumer will not wait for all the data to arrive at once.

🎯 Ending Notes

I hope this post helped you understand the basics of Reactive Programming in Spring applications. I have made all the code changes used in this article available at my GitHub repository here. The repository also has CRUD operations performed in Reactive way, using ReactiveMongoRepository, with functional endpoints.